I went to see Red Tails yesterday, without having read any reviews of the movie. I went because I saw George Lucas on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart explain how difficult it had been for him to get the picture made, saying “Hollywood isn’t interested in a film with an all-black cast.

I went to see Red Tails yesterday, without having read any reviews of the movie. I went because I saw George Lucas on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart explain how difficult it had been for him to get the picture made, saying “Hollywood isn’t interested in a film with an all-black cast. My mailman, on the other hand, took his 13-year-old son to see it last weekend, when it opened. The youngster told his dad it was “the best movie he had ever seen.”

I am in favor of any movie that sets out to portray African-American heroes who aren’t totally fictitious and based on wishful thinking. The Tuskegee Airmen, the “experiment” in the U.S. Army to test the widespread belief that Negroes were innately inferior cowards who either couldn’t or wouldn’t stand up in the face of life-threatening combat, were and remain bona fide war heroes.

I was born six months after May 1944, the date stated at the start of the movie. My bio-father and all the other age-eligible men in my family were not there for my arrival because they were fighting in World War II. With my frame of reference so tied to the events covered in the movie, I was instantly along for the ride.

George Lucas is known for spectacle -- epic stories told with eye-boggling special effects. I might be wrong, but I don’t think he is the first movie producer who comes to mind when we think of pithy dialogue, historical detail or exemplary dramatic acting.

The story is becoming better known than it had been before HBO produced The Tuskegee Airmen made-for-television movie in 1995. A 1925 Army War College report concluded that African Americans might be effective soldiers, but maintained that "in the process of evolution, the American Negro has not progressed as far as the other subspecies of the human family." (Red Tails opens with a quote from this report.) “Colored” men, it held, were both physically and intellectually incapable of enduring the demands of combat, much less flight. And, they lacked bravery, the report claimed.

“Although African Americans had valiantly served in the Civil War, on the frontier in the Indian Wars, in the Spanish American War and in World War I, white politicians and military officers still publicly professed to doubt black ability and patriotism, as part of the ideology and propaganda that undergirded Jim Crow in all of its pernicious forms. The crucial change came in 1938, primarily because of the efforts of an African-American woman, Mary McLeod Bethune, who saw, before most other black leaders, a way to break the hold of racism on black participation in the military, by striking at the most resistant obstacle of all: the integration of the pilot program.” {The Root.com, 1/25/2012, Henry Louis Gates, Jr.}

The movie uses the quote from the War College report as the film’s jumping off point, apparently giving the audience generous credit for knowing their Black History.

I watched the movie as a clueless movie fan, without giving much thought to what critics might think. I was, at times, breathless with the excitement the cinematography provided. The video game quality of action we have come to expect from deftly-applied CGI is a major part of the film. One can easily see why a 13-year-old boy would find it captivating.

I left the theater very pleased. I had been entertained. I had seen at least passable acting, although I am starting to question what the very busy Terrence Howard brings to the table besides his undeniable fineness of face. I had fun, like I used to when I went to action movies with war themes.

There was, however, only one character who seemed to be bothered by the actual result of his unit’s heroics – the flight captain. It is fitting that he would have developed a drinking problem as a result of his concerns, but I had to conclude all that for myself, because the script never really makes the connection. The young pilots regarded their targets the same way our gaming children look at targets on their X-Boxes. There is no regard at all for the humans who are manning the ships they blew up or flying the enemy planes they shot down with glee. I told myself I was trying to be too evolved for the genre.

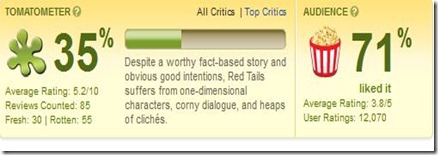

I came home and immediately searched out the critics’ opinions. Rotten Tomato.com was my first stop. I was stunned to see that most professional critics had panned the film. Fifty-five of the 85 critics who reviewed it, gave it negative reviews.

While not standing on their stadium seats cheering, the paying audience liked the film far more than they didn’t. And look at this:

Those movies that received the highest ratings last weekend also took in the least amount of money. And Red Tails came in second!

My theory is the following:

- Movie critics take themselves way too seriously. Not every film has to be laden with historical context at the expense of entertainment. This film is more like a super hero flick, in the fashion of Dark Knight (Batman) and Iron Man. The difference is it attempts to stay true to the 1940s.

- The one-dimensional character charge is unfair, given the intent of the film. No, we don’t learn the backstory of each of the pilots. Neither do we learn the slings and arrows the officers played by Howard and Cuba Gooding, Jr. suffered to attain their ranks. Do we really need to?

- One of my stepfathers fought in the Japanese theater of WWII. He came home from the war with a “souvenir”-- the dagger he had used to slay a Japanese soldier in hand-to-hand combat, blood stains intact. He spoke a language that was pure military. It was as corny as hell. That’s the way they talked back then. But the average age of the critics who reviewed the film on Rotten Tomatoes is probably at least half of mine. What would they know about the veracity of the dialogue? Roger Ebert, on the other hand, critic extraordinaire and a man of a certain age, rated the film much more positively.

- Does every film that deals with race have to be somber and reverent, true to every aspect of what has gone before? Maybe, just maybe, we can teach a lot more white audience members more about black history if we don’t try to bludgeon them with deep historical dives. This story speaks for itself. Brave people lobbied for a chance; when given the chance, the pilots rose to the occasion; and the white pilots they protected and escorted to their destinations while fighting off enemy fire were damned happy to see them when they showed up.